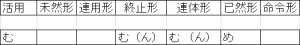

The auxiliary ~む is quite potentially one of the most complicated auxiliary verbs, but it is also one of the most common. It is called an auxiliary verb of conjecture (推量助動詞)and its meanings, while various, relate to statements that are indirect or not completely certain. It is governed by the mizenkei and conjugates as a defective yodan verb lacking a mizenkei, ren’youkei, and meireikei. It always occurs as the final auxiliary verb.

First, I’ll go over it’s various uses. As a forewarning, I’ve gone through various sources and reorganized all the uses I could find under my own system. I feel that my system groups closely related meanings while keeping distinct grammatical moods separate. Because Japanese lacks native words to denote many grammatical moods, I’ve re-translated some of the established Japanese usage names and created a new term to make a uniform system.

This is the most basic use. This mood shows a medium degree of doubt as to what is stated. It also has no relation to tense or aspect. When it occurs alone, it makes a conjecture about some event. It can be translated as 「だろう」.

Ex) 明日雨降らむ。(明日雨が降るだろう。)(It will probably rain tomorrow.)

This use shows the speaker’s desire to act in a certain manner. It can be translated as 「つもりだ」or as the modern volitional when used with 「思ふ」.

Ex) 我京に行かむ。(京都に行くつもりだ。)(I intend on going to the capital.)

Ex) 雪ふみわけて君を見むとは (雪を踏み分けて、陛下を見ようとは{思った})(I thought “I shall trudge through the snow to see my lord.)

This use shows a speakers desire to act and induce another party to do the same. That is, it means “let’s.” Therefore, we will translate it as the modern volitional. I’ve given this mood a separate name 「きょうかんゆう」, 協 meaning “co-” and 勧誘 a preexisting word referring to another use explained below.

Ex) 桜見に行かむ。(桜を見に行こう!)(Let’s go see the cherry blossoms!)

- 赴勧誘 Adhortatory Mood (frequently referred to as “inducement”)

This use usually corresponds to the from 「こそ。。。~め。」The meanings of this use all denote the speaker’s urging to have a second or third party act in a certain way. It is mild in degree, so a translation like ~た方が良い is suitable as an indirect command, also as a suggestion 「~たらどう?」(what if?) , and as an invitation 「~ない?」(won’t you?).

Ex) 鳥こそ鳴り止まめ。(鳥よ、鳴るのをやめた方が良い・やめて欲しいのだが。。etc.)(Oh bird, you ought to stop chirping!)

- 婉曲推量 Periphrastic Dubitative Mood

This usage is always in the form of the rentaikei. As both attributives and substantives, this use indirectly states things, giving a dubitative attribute to the word it modifies. Essentially, it’s the same as it’s dubitative usage if the modern Japanese equivalent could sentence-modify. It can be translated as (だろう)「という」「ような」or 「というような」, but it is often difficult to translate well.

Ex) 秋は限りと見む人のため (秋は終わっていると思うという人のため)(for those who may see autumn as having ended)

花の散らなむ後(のち)(桜の花が散っただろうという後)(after the cherry blossoms may have fallen)

The form ~めや (izenkei + や), which is used in 和歌, poses a rhetorical question. That is, the answer is the opposite to what is suggested.

Ex) その時悔ゆとも、甲斐あらめや。(その時に悔しく感じるとしても、意味があるだろうか。{いや、ない})(Even if he feels regret at that time, does it have any meaning? {no, it doesn’t}).

The Pronunciation of ~む

Relatively early on, ~む frequently lost its vowel in speech and became “m” or “n,” but since this happened before the creation of syllabic “n” 「ん」, the writing of ~む persisted. Due to this, many sources romanize forms such as 「ゆかむ」 as “yukan.” Either pronunciation is fine when reading aloud. Be careful when reading classical texts written with 「ん」and make sure to translate it as ~む and not as 「~ぬ」, the rentaikei of ~ず.

The Development of the Modern 推量形

The 推量形 of modern Japanese, that is, the form that ends in う or よう (話そう・見よう)is actually a contraction (different from the one above) and sound change of a verb ending in ~む. It is for this reason that there are a lot of similarities in meaning between these forms. It also explains why that form cannot take on further endings. Let’s see the process:

帰る -> 帰らむ ->elision of “m”-> 帰らう -> classical pronunciation of dipthong “au”-> 帰ろう (modern pronunciation)

Due to this, during the Edo Period especially, verbs ending in what we recognize as the volitional mood carried all the conjectural meanings of ~む. Recently, its uses were split between ~よう and ~だろう in order to create a tentative mood separate from the volitional/hortatory. One verb that carries all of the original meanings, however is 「ございましょう」. Since there is no current form that is ござるだろう, and ござる is always kept in ます form, ございましょう remains as a relic meaning “there probably exists (hum)”. The use of ~よう・~ましょう for the dubitative mood can also be heard in many Edo Period dramas.