The auxiliary verb ~(え)り is an auxiliary of aspect. It occurs only with yodan and sa-hen verbs as well as frequently with subsidiary verbs of politeness. After the Kamakura period, it was also attached to the ren’youkei of shimo-nidan verbs. It conveys the perfect continuous aspect (“have” “has been” 「ている」「てある」).

There are some sources which say that ~り is an auxiliary bound by the meireikei, but this is entirely false. To find out why some say this is, we have to look to Old Japanese, the stage of the Japanese language before Middle Japanese (CJ).

There existed in OJ more than the 5 vowels we are used to. Though the exact number and nature of these vowels is contested, it is generally agreed that there were 8. Amongst those were two versions of /i/, designated as i1 and i2. We know this because there are certain man’yougana /i/ that are used only in some places, and others that are used in other places. The same goes for /e/, for which there existed two variants, e1 and e2.

Knowing that, we must think logically: 1) why would an auxiliary of aspect be bound to the meireikei when all others are attached to the ren’youkei? 2) why do the man’yougana show ~り attached to what appears to be the meireikei?

Regarding #1, it makes no sense that of the numerous auxiliaries, only one would attach to the meireikei. Furthermore, why would ~り be attached to the ren’youkei of shimo-nidan verbs in later stages of the languages?

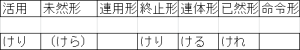

The answer is that ~り was actually あり. When it followed the ren’youkei of these verbs in OJ (which we can deduce from both its later use and the fact that all other auxiliaries of aspect follow the ren’youkei), the /i/ of the stem and the /a/ of 「あり」 monophthongized into /e/. More specifically, i1 + a = e1 where i1 is the terminal vowel of the ren’youkei (we’ll see this again with the noun *あく and the auxiliary ~けり, which further proves this point). It happens that e1 was the terminating vowel of the meireikei (e2 was the izenkei) and so, since these vowels always monophthongized, the resulting word was written the way it sounded, and it happened to appear to be the meireikei. When e1 and e2 merged into え at the end of the OJ period, this further made things ambiguous, resulting in yet other sources faulting to saying that ~り followed the izenkei.

For the sake of summarizing that in the context of CJ, the suffix ~り is actually ~あり and it is attached to the ren’youkei. However, the vowels monophthongize into え, and so the result is ~(え)り.

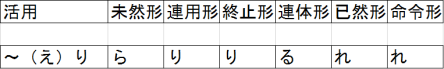

~(え)り is therefore of the ra-hen conjugation:

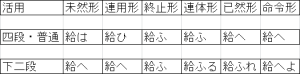

The mizenkei was only followed by ~む and became the auxiliary ~らむ. The ren’you, izen, and meireikei were seldom used, but most often with the verb 給ふ・たまふ. Additionally, when it is added to 「持つ」, the result is sometimes 「持たり」, not the expected 「持てり」.

Examples:

雪いと白う降れり。(雪がとても白く降ってある。)(The snow, so white, has fallen.)

み吉野の山辺に咲ける櫻花、(吉野の山の裾に咲いている桜の花、)(The flowers at the base of Mt. Yoshino have bloomed,)

妻もこもれり、我もこもれり、(妻もこもっており、私もこもって、)(My wife has secluded herself, and I have too,)

花持ちて上り給へり。(花を持って上京なさっている。)(She, carrying the flower, has gone to the capital.)